I’ve been preaching through Exodus since December 2023. This Sunday will be my 46th sermon on the book, so I’ve gotten quite familiar with it, to say the least. As I’ve come to Exodus 34 though, the question of republication has reared its head again.

As long as I remember having known about the controversy, I’ve been incredulous about the idea of a formal republication of the covenant of works. Although some would disagree with this evaluation, the Westminster Confession of Faith is quite clear about the role of the Mosaic covenant in redemptive history, and I have had no reason to doubt the Confession on this point. In fact, all of my study has tended to confirm that belief.

But Exodus has caused me to stumble over a few things. Particularly, I’ve struggled with how to deal with how the covenant in Exodus 19-24 fits into the covenant of grace scheme. What follows are my observations about the text which have raised these questions, and my current thoughts on the matter.

The Nature of the Covenant in Exodus 19-24

The narrative in Exodus 19-24 describes the situation surrounding the inauguration of God’s covenant with Israel, as well as the stipulations of the covenant itself. There are two features in the text that point to this covenant having a significant works principle.

First, the covenant is explicitly conditional. Exodus 19:5-6 says,

Now therefore, if you will indeed obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession among all peoples, for all the earth is mine; and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.

The key word here is, of course, if. In order to receive the covenant promises, the people of Israel must continue in obedience to the covenant stipulations. Second, the covenant is bilateral. Twice the people of Israel agree to observe the law of the covenant (Ex. 19:8, 24:3). Israel voluntarily agrees to these stipulations as the condition for receiving the promises.

One principle of biblical interpretation is that promises imply the opposite threat (WLC 99). If that applies in this case, then the opposite threat is included in this promise: if you fail to meet the conditions, you will not receive the promise. This is, of course, exactly how the covenant of works was established. God promised to reward Adam with obedience if he obeyed and death if he disobeyed.

New Creation in the Tabernacle Instructions in Exodus 25-31

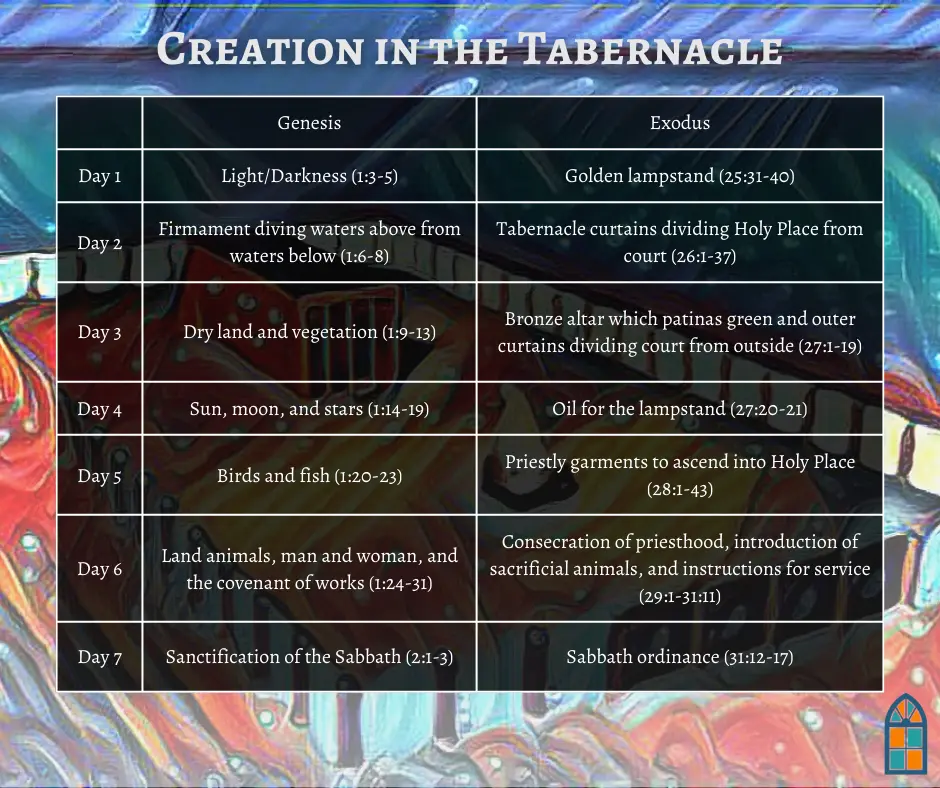

Immediately following the inauguration of the covenant, Moses ascends the mountain to receive the plans for the tabernacle. These plans again bring us back to the creation. The tabernacle is modeled after the six days of creation, and the section concludes with repeated Sabbath laws, just as creation ended with a Sabbath. The chart below gives the basic outline.

So by the time we get to Exodus 32, Moses has placed us in a Genesis frame of mind. He has tied us back to Adam’s state of innocence. In a sense, we might say that Israel has received a clean slate by this covenant.

This is motif is somewhat common throughout the Old Testament. To take one example, when Noah leaves the ark, he enters into a new creation with the same mandate that Adam received, and he immediately fails the test of faithfulness by his drunkenness. Well now, Israel has a test of faithfulness: will they obey?

Edenic Parallels in Exodus 32-33

Exodus 32 and the first part of 33 describe the golden calf narrative. Since we are already thinking about the garden, the parallels to Adam’s fall are striking. The story begins with Israel seeking something she cannot have. She seeks to create her own gods, just as Eve seeks to become like God. The word used to describe Moses delay is normally translated “shame,” which seems to get to the bottom of Israel’s problem. They’re embarrassed because they’ve followed a prophet into the wilderness and they don’t know (what tree did Eve eat from?) where he has gone.

Being resolved to sin, they turn to the man who was left in charge, Aaron. What Aaron should have done was stop the evil, but instead, he indulges it, just as Adam listened to his wife and fell in sin himself. And when Moses confronts Aaron, Aaron recapitulates Adam’s blame game, first blaming the people themselves and then claiming that he wasn’t really responsible for the golden calf.

One other parallel comes clear in the King James translation. Exodus 32:25 says,

And when Moses saw that the people were naked; (for Aaron had made them naked unto their shame among their enemies:)

The word for naked is usually translated “loose” or something similar in modern translations, but given that Israel’s idolatrous feast was probably orgiastic, naked is probably an appropriate translation. Their nakedness/looseness/uncovering is then said to be a shame to their enemies. Adam and Eve in their sin found themselves similarly naked and ashamed.

There may very well be more allusions. For example, are the Levites carrying their swords supposed to remind us of the cherubim guarding the garden by the sword? We could very well debate about how closely these two stories align with one another, but I think the broad connections are very clear.

But the whole thing comes together with God’s punishment on Israel. Moses breaks the tablets, symbolizing the rupture of the covenant, and God quite emphatically separates himself from Israel. He tells Moses that Moses cannot atone for the people’s sin. He has Moses build a tent outside of the camp. And, most importantly, he tells the people that his presence will not go with them. This is the judgment which is contrary to the promise in Exodus 19 that Israel would be God’s treasured possession.

So it seems that one major point of Exodus 19-33 is to demonstrate that Israel is recapitulating Adam’s fall and breach of the covenant of works.

The Nature of the Renewed Covenant in Exodus 34

At the end of Exodus 33, Moses turns to God and makes several requests. This is typological of Christ’s intercession, and ends with the revelation of God’s glory to Moses. Having seen God’s glory, Moses asks for forgiveness, and God responds in verse 10:

And he said, “Behold, I am making a covenant. Before all your people I will do marvels, such as have not been created in all the earth or in any nation. And all the people among whom you are shall see the work of the LORD, for it is an awesome thing that I will do with you.

There are several features which distinguish this covenant from what we find in Exodus 19-24. First, the earlier covenant was made with Israel as a whole, and it is unmediated. At Mount Sinai, God speaks verbally and directly to the people of Israel. The covenant does not seem to have any particular interest in Moses. But now, Moses has clearly been distinguished as a mediator for the people. He, of course, demonstrates this role in his intercession, but take note of the way God speaks in the verse above: all of the “you” pronouns are singular. This covenant is made particularly for the benefit of Moses as mediator. Only later on, in verse 27 is Israel mentioned with respect to the covenant, and there God says that the covenant is made “with you and with Israel.” This is not unlike how the covenant of grace is made with Christ and his elect seed in him (WLC 31).

This special role in the renewed covenant is confirmed by Moses’ shining face. The glory of God is hidden from Israel, but Moses reflects the glory of God to the people as he speaks to them. The Christological typology here is obvious.

The renewed covenant in Exodus 34 is also unilateral. At no point is Israel expected to consent to this covenant as in the previous. Instead, God simply makes promises. There is not conditional statement attached. And when God does repeat various laws to Moses, the laws he chooses are all drawn from the first table. In other words, if there is any condition to this covenant, it seems that the focus is on faith (as opposed to apostasy).

Conclusion

To bring this all together, the conclusion I’m circling around (but am unwilling to commit to at this point) is that there may be some kind of formal, not merely material, works principle in the covenant described in Exodus 19-24. However, the Mosaic covenant is not limited to those chapters. When God renews the covenant in Exodus 34, any works principle that may have existed seems to be wiped away by Moses’ intercession. In other words, the Mosaic covenant is properly understood as an administration of the covenant of grace, not an appendage as some suggest.

The one remaining question I have is whether these two covenants are substantially the same. In other words, is Exodus 34 a renewal of the Exodus 19-24 covenant, or is he making an entirely separate covenant which is more properly an administration of the covenant of grace? My inclination, admittedly in the interest of being cautious, is to see these as a single covenant which is being revised on account of Israel’s problems.

In the various authors I’ve skimmed to solve this conundrum, Exodus 34 is rarely treated with any depth, if at all. If anyone knows of someone who has treated this text well, please let me know.