Do American Presbyterians have a liturgical heritage? This is a question that is very difficult to answer. Relative to similar Protestant traditions in America, Presbyterian worship is on a much broader spectrum of diversity. Episcopalians, Lutherans, and the Dutch Reformed all have strict service books. Presbyterians are in a different situation entirely. The mainline church has her Book of Common Worship, but it is not well-used. As I surveyed church bulletins from several PCUSA churches in my area and beyond, I was able to find only a small handful who followed the service order outlined by the Book of Common Worship. And it seems the churches that do closely follow the book are very much on the progressive end of the denomination.1 Most of the evangelical churches do not even have a similar service book. In fact, the largest evangelical Presbyterian denomination, the PCA, does not even have a binding directory of worship.2 But how did we get here?

This paper seeks to answer at least part of that question by examining the history of worship in the Presbyterian Church during the second half of the nineteenth century. In particular, we will see the growing interest in formal service books from 1855, the year Baird’s Eutaxia was published, to 1903, the year the PCUSA first authorized the production of a Book of Common Worship. This paper contends that this era was characterized not by innovation, but by retrieval, not by a rejection of Presbyterian standards and history, but by obedience to both. Presbyterian do in fact have a liturgical heritage, and the liturgical movement of the nineteenth century was primarily an attempt to return to that heritage for the sake of the Church.

This paper will be especially interested in the liturgical works produced by Presbyterians in this period. We will consider the content of several of these to observe the various streams of concern they represent. We will also look at the primary source material related to these debates, both academically and ecclesiastically. Furthermore, I am greatly indebted to the work of Julius Melton, perhaps the scholar who most prolifically studied these questions.

First, we will discuss the state of worship leading up to 1855. Second, we will observe the way Charles Baird’s Eutaxia led to a litany of litanies leading up to the twentieth century. Finally, we will see how this explosion in interest led the Northern Church to move toward approving more detailed liturgical resources.3

The State of Worship in the Eighteenth Century and the Reforms of 1788

When British Reformed settlers first arrived in the New World, their worship was largely representative of Old World worship.4 At the same time, worship took on a more frontier character and tended to shade in a radical Puritan direction. Several factors may have contributed to this (geography, lack of ministers, anti-Episcopal bias), but by the time of the formation of the first General Assembly in the United States, work was being done to remedy some of the less decorous trends in American Presbyterian worship. The draft version of the 1788 Directory for Public Worship is reflective of this.

There are several items of note in this draft. First, the draft of the Directory has a uniquely ecumenical spirit. There is an expected place of honor held for Congregational and Continental Reformed churches, but Episcopal and Lutheran churches are also recommended as legitimate options for those in places without Presbyterian churches.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. 1787, 51) Second, the draft lists a variety of complaints against standard practices of the time. Among these practices are (1) entering and leaving the service at will, (2) a lack of congregational singing, and (3) outward shows of disinterest in public prayer, Scripture reading, and preaching. The authors of the Directory were concerned with a general lack of reverence in worship and wanted to see the Spirit-filled nature of worship reflected in outward forms, noting,

“It is readily granted, that there may be the appearance, without the spirit of devotion; but there cannot be the spirit, without the appearance: and, did we attend more to the appearance, it might have a happy tendency to awaken and revive a devotional spirit.”(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. 1787, 52ff)

Apparently, these problems were common enough in Presbyterian worship that the Directory’s authors felt compelled to address them. This is confirmed by contemporaneous accounts. One such account is from Charles Woodmason, an Anglican who served Presbyterian pulpits in rural South Carolina. Woodmason mentions a variety of interruptions in worship ranging from the mundane, such as whispering or spitting tobacco, to the ridiculous. In one case, he describes a group of disruptors who put together a dog fight.(Bynum 1996, 160)

At the same time, one could hardly blame the more pious of these folk for their struggle to participate. Services were frequently two hours long. The bulk of that time was consumed by a thirty minute lecture on a passage of Scripture in addition to an hour-long sermon. Often, sermons were based on very small portions of Scripture, two verses or even less. Scripture reading was reduced far below the original Directory’s recommendation of one chapter from each testament. Singing was unpleasant and confused with poorly trained precentors bickering with congregants about tune choices (of which there were, optimistically, a dozen options). The congregation was also expected to stand for prayers upwards of twenty minutes in length.(Bynum 1996, 158ff)

Some of these concerns were directly addressed in the draft Directory. With regard to the length of sermons, the draft recommends thirty to forty-five minutes.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. 1787, 75) It also reaffirms the preference for longer Scripture readings, at least one chapter from each testament. The minister’s discretion was limited; he may only lengthen, not shorten, the readings. The traditional practice of “lining out” psalms with a precentor was discouraged in favor of having printed copies of the music.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. 1787, 59) In all, the general tone of the draft suggests a reduction of preaching in favor of other elements of worship. This, of course, does not imply that preaching was de-emphasized. Arguably, the committee was aiming for a higher form of preaching. They encouraged more careful and faithful use of Scripture as well as better preparation:

“This method of preaching requires much study, meditation and prayer. Ministers ought, in general, to write their sermons, and not to indulge themselves in loose extempore harangues, but to carry beaten oil into the sanctuary of the Lord.”(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. 1787, 73)

It seems as if the committee considered long, extemporaneous sermons on small passages of Scripture to be a poor method. The expectation that sermons be written was intended to aid in careful preparation. In fact, the committee goes on to discourage the use of any notes in the pulpit.

One of the more contentious elements of the draft Directory was its use of written prayers. The draft contains various extensive forms of prayers. These are clearly intended as examples, not required forms, but it was a deviation from the original which carefully avoided forms. The major exception is the recommended use of the Lord’s Prayer at the end of the prayer before the sermon. The Lord’s Prayer was included in the original Directory as well, but its use was probably uncommon among Americans (likely for anti-Episcopal reasons).(Bynum 1996, 158)

Ultimately, many of the reforms suggested by the committee revising the Directory for Public Worship went too far for the Synod. The revision was wide-ranging and comprehensive, reflecting developments from the 1644 Westminster Assembly. American Presbyterians seemed to recognize that their tradition needed to be reformed to meet the needs of the new nation, ameliorating uniquely American abuses and encouraging biblical piety. Thus, while many revisions were accepted, more drastic changes were rolled back by the Synod in 1788. The committee had made a valiant effort at reform, but their hopes would not be fully realized for some time. The habits and forms driving American worship had already become too strongly ingrained in Presbyterian congregations for sweeping changes to take root at the level of higher church courts, much less among scattered, rural congregations on the frontier.(Melton 1967, 18)

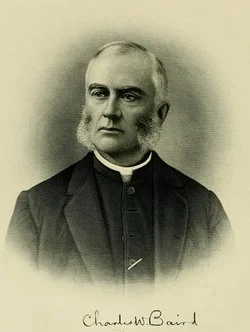

Charles Baird’s Eutaxia

Of all contenders, Charles Baird was uniquely positioned to address the liturgical problems of nineteenth century Presbyterians. His father, Robert Baird, was an Old School Presbyterian minister from the frontier; however, Charles spent many years of his childhood in Europe where his father served the Foreign Evangelical Society. This strong doctrinal foundation and broad exposure to various forms of Protestant worship gave him the tools to address the American Presbyterian church well. In 1855, he took on this challenge with the anonymous publication of his Eutaxia, a book of historic Reformed liturgies accompanied by Baird’s extensive commentary.(Old 1988, 260–61)

Baird’s work is impressive on several fronts. First, it is a formidable work of history in its own right. Eutaxia contains liturgies from several regions and languages across almost three centuries. Each liturgy contains an introduction and extensive notes. A perusal of Baird’s sources reveals that he was widely read in even very obscure documents from a large number of Reformation figures. Second, these liturgies were not unknown to Reformation scholars, but Baird made them accessible. Many of these liturgies had never been translated in English.(Old 1988, 261–62)

But perhaps Baird’s most important contribution, and part of what made Eutaxia successful, was his clear articulation of Presbyterian principles. At this point in history, Protestants were dealing with major efforts at liturgical reform that were coupled with significant departures from Protestant theology. On one hand, the Oxford movement was rising among Episcopalians, and on the other, Mercersburg theology had gained ground among the German Reformed and was getting the attention of Presbyterians. In particular, the theological rift between Charles Hodge of Princeton and John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff of Mercersburg was wide and clearly-defined by 1855.5 Thus, Hodge’s positive review of Eutaxia was weighty. He offered almost complete affirmation of Baird’s work, and offers the following conclusion:

“These two conditions being supposed, first, that the book should be compiled and not written; and secondly, that its use should be optional–we are strongly of opinion that it would answer a most important end.”(C. Hodge 1855, 460)

It is difficult to imagine a stronger endorsement of Baird’s project, which, coming from such a highly respected theologian, would have been an enormous boon.

Baird says his purpose in preparing the book is “[to] ascertain from the history and teachings of the Presbyterian Church, what may be considered its proper theory of worship; and to compare that ideal with our prevailing practice...”(Baird 1855, 1) He goes on to speak with utmost respect for the tradition of the Directory for Public Worship. He is very keen to show his Presbyterian bona fides. In this way, Baird’s project was very much unlike Oxford and Mercersburg which sought to expand the bounds of Reformed theology; instead, his desire was to work within the space provided by the Directory. He finds help in this by citing passages directly from the Directory and reputable theologians in the American Presbyterian tradition.(Baird 1855, 6–7)

Furthermore, Baird developed categories to help frame the Presbyterian approach to liturgical forms. He defines four “methods,” (1) imposed ritual, (2) discretionary ritual, (3) rubrical provision, and (4) entire freedom. The third position is represented by the Directory. But while (1) and (4) are outside of the bounds of Presbyterianism, according to Baird, “discretionary ritual” has a strong pedigree. Baird includes examples such as the old practice of the Church of Scotland and the failed 1788 revision of the Directory itself.(Baird 1855, 8–9)

After developing these views in his introduction, Baird continues by giving a series of discretionary liturgies along with his commentary. In another wise move, the majority of these liturgies are drawn directly from the Presbyterian and Reformed line. He includes Calvin’s Geneva liturgies, the liturgies of Knox and the Church of Scotland, and both Conformist and Nonconformist Puritan liturgies. Names like Calvin and Knox could hardly be offensive to any self-respecting Presbyterian!

The impact of Baird’s work would prove to be immense. What began as a modest proposal based on historical work sparked an explosion in liturgical thinking among Americans. One scholar notes that Presbyterians were “startled” by Baird’s work.(Hall 1994, 71) Prior to 1855, there were almost no Presbyterian prayer books in existence, but after Eutaxia, Presbyterians were suddenly more willing to engage with more structured forms of worship. As we will discuss soon, agitation was already building among clergy and laymen alike for accessible forms in Presbyterian worship, but Baird’s work provided both theological and historical rationale to engage in the project unabashed. As the timeline below shows, Eutaxia set off a half-century of liturgical thinking and sparked the production of a number of unofficial prayer books for Presbyterian worship.

A Litany of Litanies

Following 1855, both clergy and lay leaders in the Presbyterian Church began to focus more attention on the production of worship books for use in their churches. The two most important laymen, Levi A. Ward and Benjamin B. Comegys, are discussed at length below. Among the clergy, however, there were a variety of approaches.

First, we may consider Charles Shields’ Book of Common Prayer as Amended by the Westminster Divines of 1661. Shields became involved in liturgical renewal during the Civil War after Union General Thomas Kane requested he produce a book of forms for use in the military. Shields showed his hand in this work by relying heavily on the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, drawing criticism for the approach. In 1867, he published the version of the Book of Common Prayer edited at the Savoy Conference of 1661 along with an introductory essay. At this point, it is worth noting that Shields’ historical argument was somewhat dubious. While there was some overlap between members of the Westminster Assembly and the Savoy Conference, these were different bodies separated by more than ten years; thus, it is probably a bit disingenuous to refer to members of the Savoy Conference as “Westminster Divines.” Shields also forcefully argued that the Book of Common Prayer belonged equally to Episcopalians and Presbyterians. Clearly, Shields had a bent toward Anglican aesthetics, and in 1889, following turmoil over his commitment to Reformed orthodoxy and other issues, Shields left the Presbyterian Church to be ordained in the Episcopal Church. While his Book of Common Prayer was received positively, it never gained much traction in the Presbyterian Church for regular use.(Melton 1967, 84–88)

A.A. Hodge, on the other hand, represented a perspective more firmly grounded in the Presbyterian tradition. Hodge’s more cautious approach gained the support of the publishing arm of the PCUSA who published his book of forms in 1877. In the introduction, Hodge gave support to the Church’s “hands-off” approach to the use of forms in worship. His book was also relatively spare. Forms were included only for occasional services, not for the regular Lord’s Day services. Any recommendations regarding Lord’s Day worship were partial. Several hymns were included as well as the texts of the Ten Commandments, Lord’s Prayer, and Apostles’ Creed, but these were never set in the context of a fuller morning or evening service.(A. A. Hodge 1882) Hodge, however, was able to set the stage for further developments as others saw the benefit in having a book of forms like Hodge’s. Over the next several years, Presbyterian ministers began to publish more complete service books, building on Hodge’s previous work.(Melton 1967, 108–9)

St. Peter’s Church, Rochester

While Baird’s work was largely historical, others in the Presbyterian Church were being more creative with liturgy. One such example is Levi A. Ward of St. Peter’s Church, Rochester, New York. Ward was a ruling elder of substantial wealth, and in the 1850s, he embarked on an impressive building project to construct a new Presbyterian church building in his hometown. As the primary benefactor, he had substantial control over the running of the congregation. Additionally, St. Peter’s was served by a succession of young ministers who were expected to conform to Ward’s wishes.(Melton 1993, 163–65)

The greatest part of Ward’s work was focused on worship reform. There is dispute over his degree of personal involvement in the project, but there is no doubt that Ward had significant influence in the preparation of St. Peter’s Church Book. The first edition of the Church Book was published in 1855, the same year Baird’s Eutaxia was published. St. Peter’s book, however, was especially designed for use in worship. It contained Lord’s Day services as well as forms for other services such as baptism, communion, and marriage. Books were provided for each worshipper as the services were designed for significant congregational participation.(Melton 1993, 164–65)

Interestingly, while St. Peter’s liturgy was certainly more complex than what one would find in the average Presbyterian congregation at the time, it was nowhere near as complex as what you would find in Episcopal churches. The morning service, for example, had the congregation participate in the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, a responsive reading, and a few hymns.(St. Peter’s Church 1855, 5–10) The 1864 edition of the Church Book expanded on congregational participation slightly, mainly through the inclusion of the congregation in more singing and chanting.(St. Peter’s Church 1864, 5–12) Perhaps the most significant “elevation” of the worship service at St. Peter’s was the heavy reliance on the choir. In both editions of the liturgy, the choir acts as a kind of third voice, singing anthems and responses throughout, but these responses were more voluminous in the 1864 edition.6

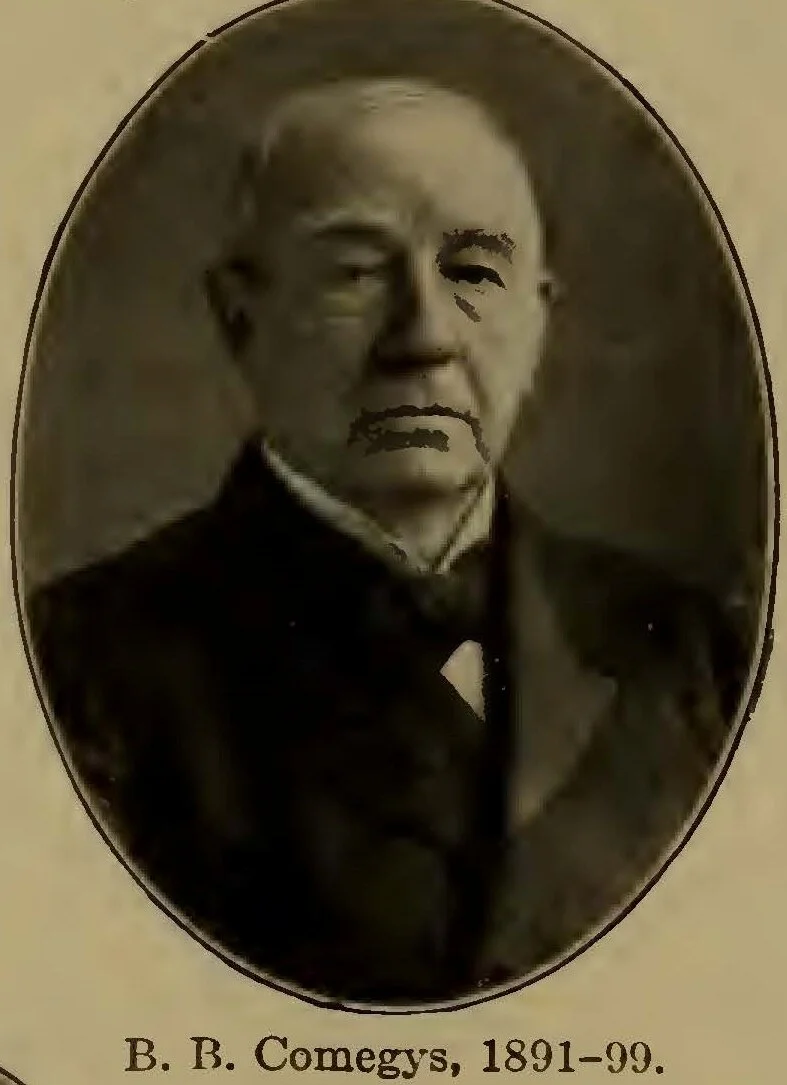

Benjamin Bartis Comegys

Benjamin Bartis Comegys was a lawyer and ruling elder from Philadelphia. In addition, he served as a lay chaplain for Girard College, a school housing orphan boys. His interest in worship was sparked by his work there. In organizing and leading chapel services at the school, he made his first foray into liturgics. In the ecclesial realm, Comegys held high church sentiments. He had a strong affinity for the formal worship of the Episcopal Church as well as for the traditional church calendar, a highly unusual perspective among Presbyterians in his day. As a churchman, he lobbied extensively for improved forms of worship, often using very strong language.(Melton 1993, 168–71)

Comegys personally compiled two service books. In 1885, he published An Order of Worship, with Forms of Prayer for Divine Service. This book contained ten Sundays worth of morning and evening services as well as various occasional forms. His sources were somewhat broad; he claims to have drawn from the services of the Church of Scotland, the Church of England, and the Huguenot Church of Charleston, South Carolina.(Comegys 1885, 3) In 1895, Comegys published a second book with a narrowed focus: A Presbyterian Prayer Book, for Public Worship. It is notable that, even in this book, Comegys had an ecumenical spirit, arguing that this prayer book was only Presbyterian insofar as its prayers largely originated in the Church of Scotland as opposed to its being grounded in Presbyterian doctrine and polity.(Comegys 1895, v-vi)

But perhaps Comegys most valuable contribution was his work in bringing the Scottish Church Service Society’s Euchologion to American shores. Comegys edited and published the book for the first time in 1867, and it underwent revisions over the course of the next forty years. It also contributed significantly in the PCUSA’s work to produce a Book of Common Worship. Comegys’ final version of Euchologion was published in 1898, just after the formation of the Church Service Society under the leadership of Louis Benson and Henry van Dyke and just before the PCUSA’s approval of a new official prayer book.(Melton 1993, 171–72) Although Comegys would die in 1900, six years before the first edition of the Book of Common Worship was published, there is little doubt that his influence was still felt by the prayer book committee, which included many members of the Church Service Society.7

Toward Common Worship

In 1897, the Church Service Society was formed at Henry van Dyke’s Brick Presbyterian Church in New York City. There had been previous thoughts at forming such a group, including by the likes of Charles Briggs, but van Dyke and Louis Benson were the first able to bring it to fruition. Both men were ministers in the PCUSA and had themselves done their own work in producing liturgical works. Louis Benson, in fact, had been the editor for the official denominational hymnal published in 1895.(Melton 1967, 120)

The Church Service Society represented a wide variety of approaches to liturgical renewal. The extremes were probably best represented by van Dyke, who was elected vice-president of the group, and B.B. Warfield. Van Dyke tended toward modernism and had a strong ecumenical streak. His father, also a Presbyterian minister, had explicitly rejected the regulative principle of worship, arguing that it was a legalistic twisting of Scripture used to support established customs.8 Furthermore, the younger van Dyke had already published liturgical materials with forms for various days in the church calendar.9 Warfield, on the other hand, was far more traditional, preferring that liturgical resources be conformed more strictly to standard Presbyterian principles. When the General Assembly assembled its committee to produce the Book of Common Worship, his caution about being overly concerned with aesthetics was not heeded.(Melton 1967, 121)

In 1903, the Northern General Assembly received two overtures regarding the production of a book of forms. One request came from the Synod of New York (notably, Henry van Dyke’s own Synod), and the other was received from the Presbytery of Denver. The Synod of New York’s overture requested that the General Assembly produce “tentative” forms of worship for the Lord’s Day. The Presbytery of Denver was more focused on forms for occasional services, not unlike the forms produced by the Southern Church in the previous decade. And once again, Henry van Dyke’s influence was key in moving these overtures forward. In 1902, he had been the moderator of the General Assembly, and in 1903, he was appointed chair of the Committee on Bills and Overtures. It is no surprise, then, that the committee recommended favorable actions on both overtures. The General Assembly unanimously approved of these overtures, and van Dyke himself was made chair of the new committee. Furthermore, a sub-committee was formed and charged with the actual assembly of a book of worship. All three members were also members of the Church Service Society: van Dyke, Louis Benson, and Charles Cuthbert.(Melton 1967, 127, 130)

Interestingly, despite unanimous approval in 1903, when a draft of the new book was offered to the 1905 General Assembly, three hours of hearty debate ensued. The consensus among detractors was that the proposed book went too far. Although the committee went to great pains to highlight the voluntary nature of the book, there were many concerns about perceived ritualism. At the end of the 1905 Assembly, the book was sent back for further revision and six new members were added to the committee for the sake of diversity. Debate continued over the course of the next year, and debate at the 1906 Assembly was just as virulent. But when time came to vote, the book was approved, although the language of “voluntary use” was highlighted.(Melton 1967, 131–34)

The Book of Common Worship, 1906

There are several items of note regarding the final version of the Book of Common Worship. First, van Dyke’s perspective on the church year seems to have won the day. In the book’s Treasury of Prayers, there is an entire section devoted to “Prayers for Certain Times and Seasons,” including prayers for Good Friday, Easter, Advent, and Christmas.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. General Assembly and Van Dyke 1906, 177ff) It is interesting that, despite extended debate about the nature of the Assembly’s approval of the book, this section was never excised, despite the Assembly’s power to do so. This seems to reflect a shift in prevailing opinions. Furthermore, despite the Southern Church’s rejection of the church calendar in 1899, the 1932 edition of the Book of Common Worship was approved for use in the Southern Church after its publication.(Coldwell and Webb 2015, 170)

Second, the book’s recommended Lord’s Day service is very conservative. With the exception of one small responsive element, the congregation’s spoken participation is limited the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. The congregation’s participation in the confession of sin is optional. Compared with the liturgies of St. Peter’s Church, for example, this form is very limited. Furthermore, there is only one morning service and one evening service; whereas, most of the books from the previous century included several examples of both services.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. General Assembly and Van Dyke 1906, 1ff)

Finally, while there is a large collection of prayers listed later, ministers are explicitly encouraged to prepare their own studied prayer. The front matter of the book contains extended instructions about the voluntary nature of its forms, and the committee goes to great lengths to point out the necessity of praying according to the needs of the congregation.(Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. General Assembly and Van Dyke 1906, vii-viii) In other words, with the exception of the inclusion of prayers for the church year, the 1906 Book of Common Worship represents a very modest effort at liturgical unity rooted in the Westminster Directory of Public Worship.

Conclusion

The second half of the nineteenth century was a unique time for the development of Presbyterian worship. Certainly, worship and liturgy were not at the front of most Presbyterian’s minds. That space was occupied by questions of race and revivalism. But through the work of a few men, American Presbyterian worship was significantly revised.

Of course, each of these men came with different concerns. Broadly, we might say there were two streams. On the one hand, many, especially certain dignified laymen, were concerned with bolstering the aesthetic quality of worship in light of growing interest in Episcopalianism. Others like Warfield and the two Hodges were concerned with theological integrity and saw liturgical renewal as one pathway to protecting a tradition under threat from revivalism and modernism. In the end, these concerns came together to produce a prayer book that respected the Presbyterian principle of liberty while encouraging more reverent and serious worship.

Their situation is not unlike what we find in twenty-first century Presbyterianism. After a period where Presbyterianism gained in popularity, we are seeing unprecedented growth in communions like the Anglican Church in North America among young people discontent with the liturgical anarchy in many Presbyterian denominations. We are also seeing a breakdown in confessional integrity, particularly with regard to the Westminster Confession’s doctrines of worship. In looking back to our nineteenth century fathers, we have a clear example of how to address these concerns. By following their lead, we may be able to see a recovery of both Reformed doctrine and piety in our day.

This is interesting to me because as a conservative confessionalist, I think the 1993 edition is quite good. Most evangelical Presbyterians would have a hard time finding anything objectionable in its regular forms.↩︎

For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on mainline Presbyterians. The Covenanters and Seceders have their own unique history of worship.↩︎

It is worth noting that this paper is, by necessity, largely focused on Northern Presbyterians, and even more specifically, Presbyterians in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. This is not a problem unique to the twenty-first century; it was, in fact, a point of contention even in some of the very debates we will discuss. In other words, much more work needs to be done in understanding the practice of and attitudes toward worship in other regions, but the South in particular, during the nineteenth century.↩︎

The term “British Reformed” is intended to include, Scots and Scots-Irish Presbyterians as well as non-conforming Puritans of various stripes.↩︎

Just one year earlier, Hodge made clear that he considered Nevin and Schaff firmly outside of the bounds of Protestantism. (C. Hodge 1854, 151).↩︎

The difference between St. Peter’s 1855 and 1864 liturgies is not dissimilar to the difference between Martin Luther’s two liturgies. See (Gibson 2018, 75ff).↩︎

In my opinion, had Comegys been alive and healthy, he would have very likely served on the committee himself.↩︎

In my opinion, this is a very strange perspective. One would be hard-pressed, I think, to accuse the Puritans of being too attached to established customs.↩︎

This was out of step with the prevailing opinions of the day. As late as 1899, the Southern General Assembly had explicitly condemned the observance of Christmas. This push by van Dyke was also only a couple of decades removed from the condemnation of Princeton professor Samuel Miller’s similar condemnations. See (Coldwell and Webb 2015, 169).↩︎