Introduction

Recent findings show that, in the Presbyterian Church in America,1 the most common exception granted to candidates for ordination pertains the Westminster Confession and Catechisms’ view of the Sabbath. In fact, exceptions pertaining to this doctrine are twice as common as full subscription in the PCA.(Lee 2024) Often, it is said that candidates have a preference for the “Continental” Sabbath view as opposed to the stricter Puritan view of Westminster. But is this an accurate characterization of the facts?

The purpose of this paper is to make a start at reviewing some of the data to help bring clarity to the question. In short, I seek to show that there is no practical difference between the Puritan and Continental views of the Sabbath. To that end, we will compare the Sabbath view of the Westminster Standards, particularly the twenty-first chapter of the Confession of Faith, against the Three Forms of Unity.

Westminster Confession of Faith chapter twenty-one gives the following summary:

7. As it is the law of nature, that, in general, a due proportion of time be set apart for the worship of God; so, in his Word, by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment binding all men in all ages, he hath particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto him: which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week; and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week, which, in Scripture, is called the Lord’s day, and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath.

8. This Sabbath is then kept holy unto the Lord, when men, after a due preparing of their hearts, and ordering of their common affairs beforehand, do not only observe an holy rest, all the day, from their own works, words, and thoughts about their worldly employments and recreations, but also are taken up, the whole time, in the public and private exercises of his worship, and in the duties of necessity and mercy.

In these two paragraphs, we may draw out three central principles:

The Sabbath command has an enduring, moral quality.

The Sabbath command particularly applies to the Lord’s Day in the New Covenant.

The Sabbath command prescribes worship of God and rest from worldly recreations and employments.

Incidentally, David Dickson observes these same three principles in his commentary on the Confession of Faith, Truth’s Victory over Error.(Dickson 1684)

Within the Three Forms of Unity, the Sabbath question is only directly addressed once, in Heidelberg Catechism 103.2

Q. 103. What does God require in the fourth commandment?

A. In the first place, that the ministry of the Gospel and schools be maintained; and that I, especially on the day of rest, diligently attend church, to learn the Word of God, to use the holy Sacraments, to call publicly upon the Lord, and to give Christian alms. In the second place, that all the days of my life I rest from my evil works, allow the Lord to work in me by his Spirit, and thus begin in this life the everlasting Sabbath.(Schaff 1977, 3:345)

Upon first glance, the Heidelberg Catechism seems far less stringent than Westminster. We have no explicit mention of the perpetual nature of the Sabbath, no explanation of the appropriate day, and no injunction against works and recreations lawful on other days. But it important to consider both context and authorial intent. Fortunately, the primary author of the Catechism, Zacharias Ursinus, produced a lengthy exposition of it as well. In this commentary, we find all three elements observed in the Westminster Confession.

Therefore, perhaps the best way to proceed is to take the content of the Westminster Confession as explained by David Dickson under three heads and compare that content with Zacharias Ursinus’ own explanation of the Sabbath which is summarized in the Heidelberg Catechism.

The Sabbath command has an enduring, moral quality.

First, the Confession indicates that the fourth commandment has both a natural law component and a positive law component.

As it is the law of nature, that, in general, a due proportion of time be set apart for the worship of God; so, in his Word, by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment binding all men in all ages, he hath particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto him... (WCF 21.7)

The key text cited by the Confession is Exodus 20:8-11. This text first contains the explicit Scriptural command: “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.”3 For the Westminster divines, the Ten Commandments constitute a summary of the enduring moral law (see Larger Catechism 98). Thus, the command here is sufficient to establish the positive law component. The natural law component is drawn from Isaiah 56, which describes eunuchs and foreigners who keep the Sabbath. The point the divines seem to be drawing from this text is that the Sabbath command extends beyond the bounds of Israel such that those outside of Israel recognize the necessity of Sabbath. The Sabbath is not simply a ceremonial institution of Israel; it is a moral law of God revealed both in nature and Scripture.

David Dickson expands on this more thoroughly. He notes five reasons for the enduring, moral nature of the Sabbath. First, the Sabbath was given as a positive, moral law prior to the fall (Gen. 2). Second, it was repeated prior to the introduction of the ceremonial law (Ex. 16). Third, it is found in the middle of the Ten Commandments by the finger of God (Ex. 20). Fourth, the reason given for the Sabbath flows directly out of God’s character as all moral laws do. The fifth reason is that Jesus, in the Olivet discourse, tells his followers to pray that they need not flee Jerusalem on the Sabbath. This is a particularly powerful argument because if the New Covenant abolished the Sabbath command, Jesus’ words are meaningless.(Dickson 1684, 190–91)

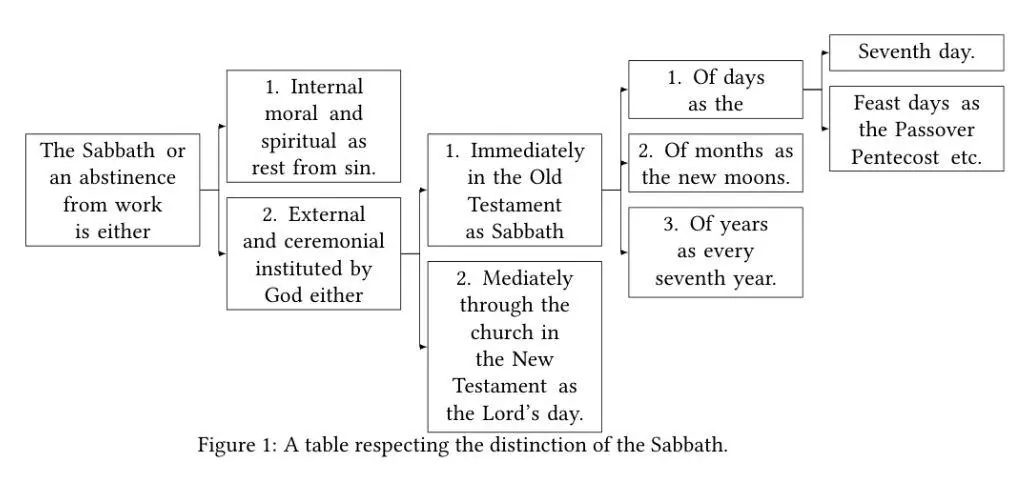

While Dickson’s exposition is relatively straightforward, Ursinus has a more sophisticated way of parsing the Sabbath command. Figure 1 is a reproduction of Ursinus’ own chart of divisions.(Ursinus 1852, 563) In short, Ursinus distinguishes between moral and ceremonial elements of the Sabbath. He then carefully distinguishes how each of these pertain to the New Testament church.

With regard to the moral element, Ursinus argues from the ends for which the Sabbath was first ordained. Namely, he lists five reasons: (1) that God may be publicly praised, (2) that public worship may stir up piety and faith in the elect, (3) that men would provoke one another to love and good works, (4) that pure doctrine and worship be preserved, and (5) that the church may be visibly distinguished from the world. Ursinus notes:

Inasmuch now as these reasons do not have respect to any particular time, but to all times and conditions of the church and world, it follows that God will always have the ministry of the church preserved and the use thereof respected, so that the moral part of this commandment binds all men from the beginning to the end of the world, to observe some Sabbath, or to devote a certain portion of their time to sermons, public prayers, and the administration of the sacraments.(Ursinus 1852, 557)

These three means of grace, Word, prayer, and sacrament, are listed in the Heidelberg Catechism as duties of the Sabbath. Ursinus, then, intends to convey that the fourth commandment requires our diligent attendance to these things, and that requirement, in turn, necessitates a day set apart.

We may then note a minor difference in the views of Dickson and Ursinus. For Dickson, the “one day in seven” is included in the positive command of God. Ursinus, on the other hand, understands the fourth commandment as simply requiring the duties of the Sabbath, not the particular time construction.4 Dickson convincingly rejects this as unbiblical, noting that the fourth commandment itself includes the six and one pattern. In any case, Ursinus seems to concede that the six and one pattern is a positive command given through the institution of the church. While Dickson and Ursinus (and, of course, the Westminster Confession and Heidelberg Catechism) reason through different paths, they end up in a similar place. Dickson understands the Sabbath as an enduring, moral command to perform Sabbath duties on one day in seven. Ursinus understands the Sabbath as an enduring, moral command to perform Sabbath duties as ceremonially prescribed by apostolic institution. Both, however, conclude that the Sabbath command has an enduring, moral quality.

The Sabbath command particularly applies to the Lord’s Day in the New Covenant.

The Confession of Faith argues that the Sabbath law previously applied to the last day of the week and now applies to the first day of the week.

...which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week; and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week, which, in Scripture, is called the Lord’s day, and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath. (WCF 21.7)

The Confession cites both the creation story in Genesis 2 and various New Testament examples (1 Cor. 16:1-2 and Acts 20:7) and injunctions for first day worship. The understanding is that the Lord’s Day is an apostolic institution.

For his part, Ursinus understands the Lord’s Day as a ceremonial application of the moral element of the Sabbath command. He contends that in the Old Covenant, the seventh day of the week was designated by divine law as the Sabbath. But the law itself does not require that the Sabbath be observed on the seventh day, simply that a day must be observed. Thus, the New Testament church has universally determined that a new ceremonial law is in effect, namely, that the Sabbath ought to be observed on the first day of the week. Ursinus argues that while this is clearly an apostolic institution, the church is not bound to any particular day. Rather, we observe Sunday in submission to the circumstantial decision of the church, under her authority. However, Ursinus never suggests deviating from this practice because of its strong pedigree and universality.(Ursinus 1852, 563)

Dickson is quick to point out an error in this line of reasoning. Those arguing for the Lord’s day as merely an apostolic and ecclesiastical institution are eliding two categories together. To use modern language, we must distinguish between the circumstances of worship which the church has authority to determine, and the elements of worship, which we receive from the Apostles. Dickson argues, that since we have both a model of Christ and his disciples meeting on the first day after the resurrection and an explicit command to perform acts of worship on the first day (1 Cor. 16:2), it is, therefore, not merely a matter of church authority that establishes the Lord’s Day.(Dickson 1684, 192–95)

Dickson understands the Lord’s Day as an apostolic institution clearly expressed in the Word of God. Ursinus understands it as a universal church tradition rooted in apostolic practice. But while Ursinus leaves room for other arrangements, practically, both men ultimately argue for first-day/Lord’s Day Sabbath observance.5 In sum, while the reasons that undergird Ursinus’ defense of a first-day Sabbath are not identical with Dickson’s, he arrives at the same conclusion.

The Sabbath command prescribes worship of God and rest from worldly recreations and employments.

The Westminster Confession of Faith summarizes the fourth commandment:

This Sabbath is then kept holy unto the Lord, when men, after a due preparing of their hearts, and ordering of their common affairs beforehand, do not only observe an holy rest, all the day, from their own works, words, and thoughts about their worldly employments and recreations, but also are taken up, the whole time, in the public and private exercises of his worship, and in the duties of necessity and mercy. (WCF 21.8)6

In this paragraph, we can identify four duties. First, the Sabbath includes the positive command to rest from engagement in worldly employments, and recreations. Second, it includes a command to worship. Third and fourth, it commands works of necessity and mercy. Here, we come to a major point of controversy. There is a high degree of unanimity concern the duties of worship, necessity, and mercy, but in recent days, it is common to hear candidates take exception to the so-called “recreation clause” in this chapter. Thus, we must answer the question, “What does the fourth commandment require us to rest from?”

On this point, Dickson, in essence, merely repeats the statement of the Confession; however, he does make the point that “ordinary recreations, games, and sports, are our own works.”(Dickson 1684, 196) His proof-text is identical with the that of the Confession:

“If thou turn away thy foot from the sabbath, from doing thy pleasure on my holy day; and call the sabbath a delight, the holy of the Lord, honourable; and shalt honour him, not doing thine own ways, nor finding thine own pleasure, nor speaking thine own words: Then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord; and I will cause thee to ride upon the high places of the earth, and feed thee with the heritage of Jacob thy father: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.” (Is. 58:13-14)

The point being made both by Dickson and the Confession is that the Sabbath ought to draw us away from our own worldly desires and into the Lord’s desires. In other words, when the Confession refers to “worldly” employments and recreations, it is speaking of merely human employments and recreations.7 These are things that distract us from the duties of the Sabbath.

This is the crucial point, and we find it repeated in Ursinus:

“[The] Sabbath is profaned either when holy works are omitted, or when such works are performed as hinder the ministry of the church, and as are contrary to the things which belong to the proper sanctification of the sabbath.”(Ursinus 1852, 566)

In the next several pages, he goes on to enumerate both the holy works required (namely, the duties pertaining to worship and acts of mercy and necessity) as well as those things that hinder these works. Repeatedly, he refers to neglect, contempt, or want of attention to Sabbath duties.

Ursinus stops short of following this logic through, but the implications are clear. He believes that the church has instituted the first day of the week as a time for Christians to observe the Sabbath. The Sabbath command requires diligent pursuit of Sabbath duties, namely, worship and acts of necessity and mercy. Therefore, to pursue our own works on this day is to take out attention from the Sabbath duties. In other words, Ursinus is in agreement with the Sabbath duties listed by the Westminster Confession, including worship, acts of mercy and necessity, and rest from worldly employments and recreations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems that we can make some summary notes. First, if we take Ursinus as representative of the Heidelberg Catechism’s intended meaning, we find that there are significant differences between the Sabbath doctrine of Westminster and that of the Heidelberg Catechism. In particular, the Continental and British Reformed depart from one another on the question of whether the fourth commandment requires a particular day be set apart to observe it. It is possible that this difference is explained by a growing maturity among the Reformed. The Heidelberg Catechism was completed in 1563 in response to Roman Catholicism; the Westminster Assembly met in the 1640s to purify an already reforming church. Further investigation into that possibility is outside of the scope of this paper, but it is a worthy pursuit.

But these things stand behind the practical concerns for Christian Sabbath observance which, of course, was the topic of our original question. The views outlined by Westminster and Heidelberg are not identical, but when it comes to top-layer question of adherence to the three principles discussed above, it is clear that all are in agreement. Thus, while we may speak of a Continental view of the Sabbath, that view is, in its outward facing conclusions, identical with the view of Westminster.

Bibliography

The Presbyterian Church in America, being the largest confessionally Reformed denomination in the United States, may act as a sort of thermometer to determine attitudes among American Presbyterians generally. It is likely, however, that this exception is far less common in other confessional denominations.↩︎

It seems the Synod of Dort did address this question, but its comments are outside of the Three Forms. See (Clark 2014).↩︎

All Scripture quotations are taken from the Authorized Version.↩︎

This is very similar to Calvin’s view. He considers the Sabbath to be a synecdoche for all the duties of proper worship. See (Calvin 1981, 177); (Calvin 2008, 2.8.32–34).↩︎

Notably, here it seems that Calvin is more in agreement with Dickson over Ursinus. See (Calvin 2008, 2.8.33).↩︎

This doctrine is explicated in more detail in Larger Catechism 115-120.↩︎

Chad Van Dixhoorn, with regard to worldly recreations, helpfully observes, “We need to find a way during the week to get the recreation we need. If we do not, we will almost inevitably find ourselves and our children pining for a second Saturday instead of enjoying our Sunday.” (Van Dixhoorn 2014, 294). For a fuller biblical argument in favor of Westminster’s view of recreation on the Lord’s day, see (Keister 2016).↩︎